I wrote about querying research papers with LLMs last February. Since then things have progressed a lot, with significant new LLM results seemingly every week. However, I think it's fair to say there is still no turnkey way to search PubMed, load a corpus of PDFs into an LLM, query, and get good quality results. (If I've missed something great, let me know...)

There are several options:

-

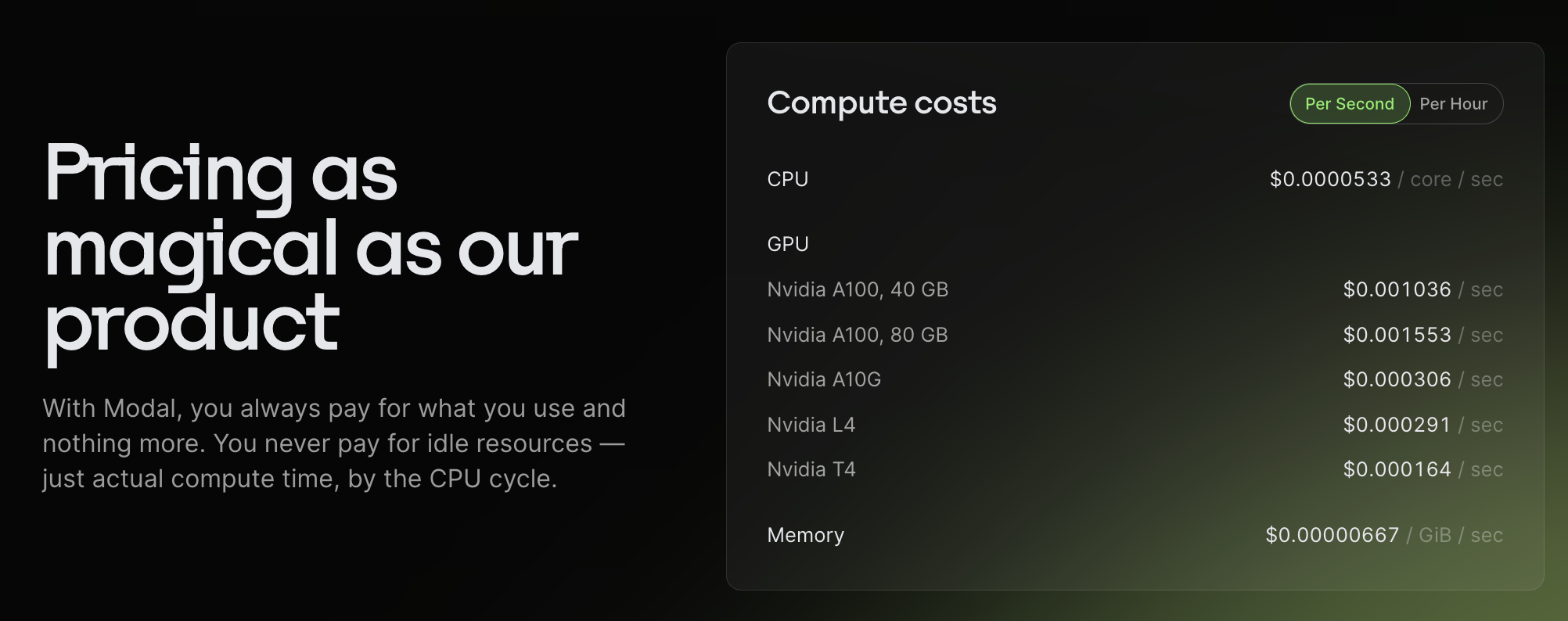

The tools I used in my previous article, Paper QA and LlamaIndex, can work well if you already have a corpus of papers. Indexing papers with GPT-4 can get expensive though.

-

New RAG (Retrieval Augmented Generation) tools like RAGatouille (which uses the new ColBERT model, now built into LangChain)

-

All-in-one local LLM UIs like gpt4all

-

Web-based scientific services like elicit.org and scite.ai. I can't tell exactly which papers these tools have access to. scite.ai seems to be focused on "citation statements" (what?) and elicit.org on abstracts. I imagine it is difficult for these services to get access to all full text articles.

As of January 2024, GPT-4 still dominates all open-source models in terms of reasoning performance, but it is expensive for larger projects, so for now I am still exploring and comparing approaches. (For various reasons, I could get neither RAGatouille nor gpt4all to run on my mac!)

Long context

One really useful recent development in LLMs is long context (>100,000 tokens, or >100,000 words, approximately). A few models now have long context: GPT-4 Turbo, Claude, and some open-source models like Anima. By comparision, GPT-3 launched with a context length of only 2,048 tokens — barely enough to hold a few abstracts.

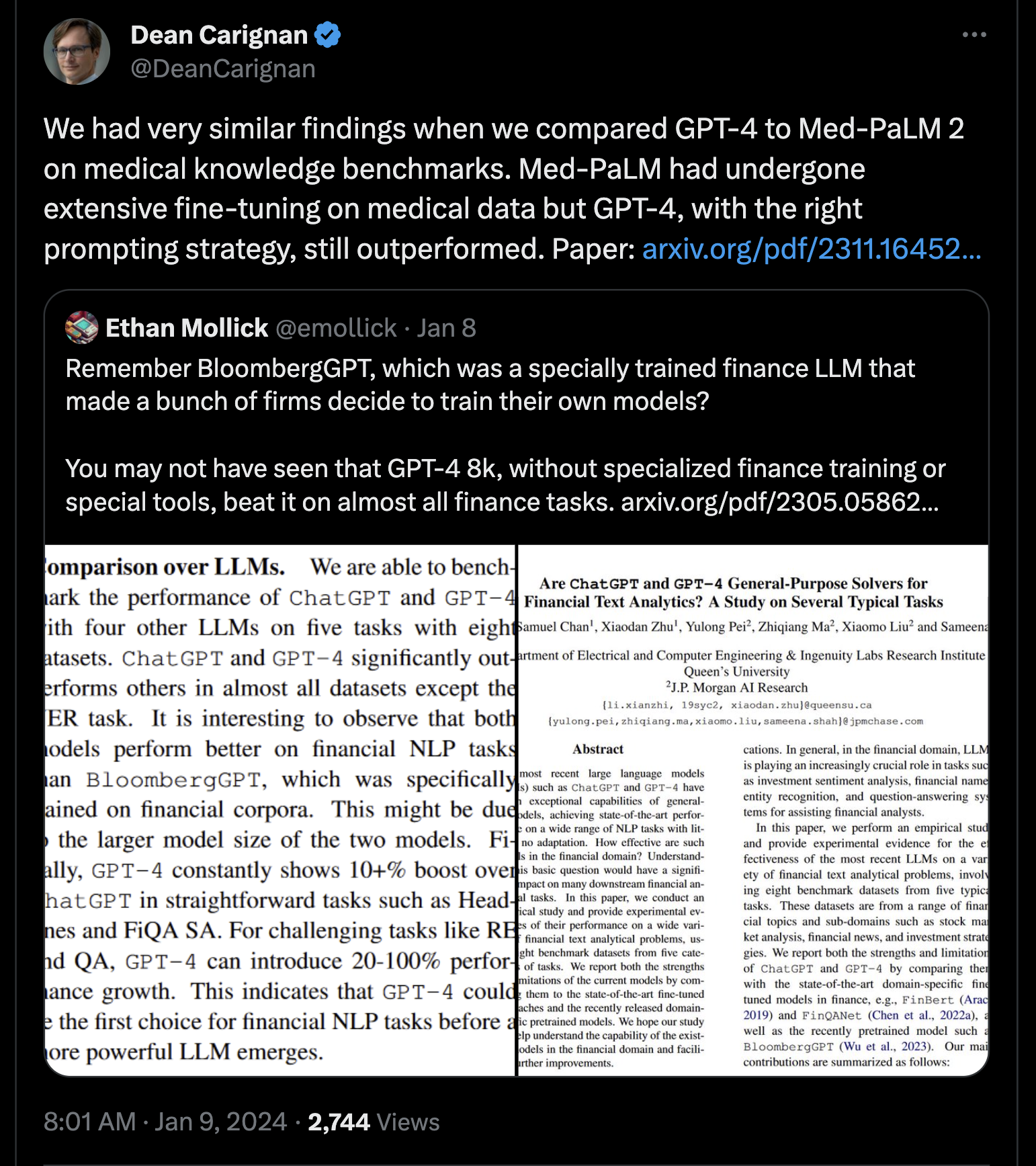

If you are trying to use an LLM to read and analyze documents, you have two main choices: you can fine-tune the model with additional training on a comparatively set of documents, or you can keep the default model and provide the document text directly in context. Perhaps surprisingly, it seems like the latter actually works fine, often better! Long context means you can directly load hundreds of pages of text into the model's memory. Intuitively, it does seem cleaner to keep the reasoning engine (LLM) separate from the domain knowledge (papers).

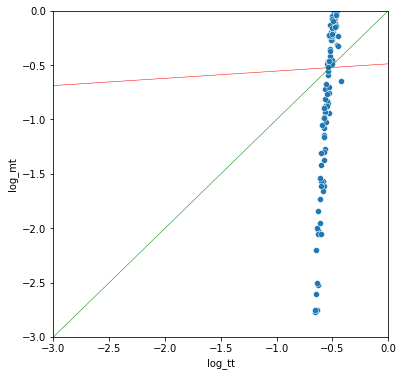

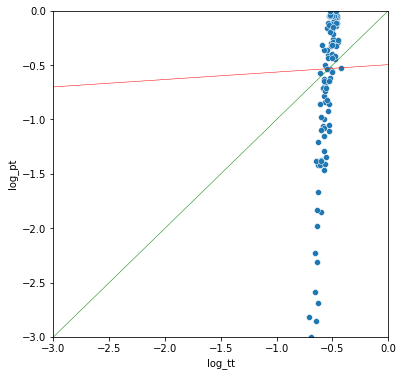

A recent post on twitter by @DeanCarignan

Notably, smaller contexts can work well with RAG, I assume because RAG pulls out only relevant passages, resulting in a better signal-to-noise ratio.

Text sources

For biomedical research, there are a few sources of text:

- abstracts, available free online via PubMed and Google Scholar

- full text papers (PDFs, HTML or JSON), some of which are available free via PubMed Central (more and more thanks to the NIH Public Access Policy)

- patents, available free via USPTO or Google Patents

- internet forums and discords. I have not actually looked into using this, but there is definitely a lot of high quality discourse on some discords.

BioC

BioC is a very useful format that is new to me. Essentially it's an NCBI-generated structured JSON file with annotated sections for "intro", "methods", etc.

Example BioC JSON

One unfortunate caveat is that I found not all PMIDs are available in BioC, even if the paper is available, so I have to use PMCIDs (PubMed Central publications) instead. No idea why, but I did email them about it.

Script

So here is a simple script that uses the PubMed and OpenAI APIs to rank a set of genes for a given "role" (e.g., ["MAP2K1", "F5"] and "cancer driver"). It searches PubMed, reads the abstracts to figure out if the gene has the specified role, summarizes the results in a JSON object, including a score from 0-10 that can be used for ranking. I found this script worked pretty well for me for ranking a few hundred genes — a task that would have been way too laborious for me to do — and it's a nice short script. The LLM prompt is far from optimized though, so buyer beware!

The long context model (GPT-4 Turbo) means I can simply include all the abstracts (I include the first 30) in the text of my query, and not worry about fine-tuning or RAG. The equivalent Paper QA script would have to additionally include an indexing and retrieval step, but could include the full text where available.

It feels strange to write these LLM scripts because most of the "code" is in English. The prompt engineering part took inspiration from Jeremy Howard from FastAI and this article from finedataproducts, which covers a lot of the same topics as this one, but in more depth.

Note that GPT-4 Turbo is still quite expensive, so although the results are pretty good, if you were attempting to search for all 20,000 genes in the human proteome, it would get expensive. Also, since you pay per token, the longer the context you provide, the more expensive it gets — proper RAG is probably a better idea for bigger projects!

Example results

Here are some results from running the script for the role "cancer driver". Note, the Summary field is an opportunity for the LLM to think "step-by-step". Surprisingly, the phrase "cancer driver" is not that commonly found with specific genes so some genes return no result.

| Gene | Cancer type | Evidence | Summary | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAT2A | Leukemia, Glioma, Gastric Cancer | MAT2A acts as an oncogenic driver by supporting methionine metabolism, crucial for MLLr leukemia (Fitzel et al. Neoplasia 2023), represents a vulnerability in H3K27M mutant glioma (Golbourn et al. Nat Cancer 2022), and protects cells from ferroptosis in gastric cancer via the MAT2A-ACSL3 pathway (Ma et al. Free Radic Biol Med 2022). Additionally, androgen-regulated alternative mRNA isoforms of MAT2A are linked with prostate cancer (Munkley et al. F1000Res 2018). | MAT2A is implicated in various cancers through its roles in methionine metabolism and impact on epigenetic regulation. The evidence is derived from several recent studies focusing on the gene’s role in promoting oncogenesis and tumor survival, with one study published in Nat Cancer revealing MAT2A as a vulnerability in H3K27M gliomas. | 7 |

| TOP1 | MYC-driven cancers | A genome-wide CRISPR knockout screen in isogenic pairs of breast cancer cell lines reveals that TOP1 is a synthetic lethal vulnerability in MYC-driven cancers (Lin et al. Cancer Res 2023). Inhibition of TOP1 leads to accumulation of R-loops and reduced fitness of MYC-transformed tumors in vivo, and drug response to TOP1 inhibitors significantly correlates with MYC levels across several cancer cell lines and patient-derived organoids. | There is strong evidence that TOP1 has a role as a cancer driver gene in MYC-driven cancers. The experiment used a genome-wide CRISPR knockout screen to identify synthetic lethal targets for MYC, finding that TOP1 is critical for the survival of cancers with high MYC activity. | 7 |

| MAP2K1 | Lung adenocarcinoma, head and neck squamous cancer, pilocytic astrocytoma | MAP2K1 mutations are associated with resistance to osimertinib in EGFR-mutated lung adenocarcinoma (Ito et al. 2023), and its expression is integrated into the APMHO prognostic score for head and neck squamous cancer (Zeng et al. 2023). MAP2K1 fusion has also been reported to activate the MAPK pathway in pilocytic astrocytoma (Yde et al. 2016). | MAP2K1 has been implicated as playing a role in cancer, with evidence pointing to its involvement in drug resistance, tumor progression, and potentially as a predictive marker. The evidence is substantial but not overwhelming. | 6 |

| BIRC2 | Cervical cancer | Chr11q BFB event leading to YAP1/BIRC2/BIRC3 gene amplification is associated with earlier age of diagnosis in cervical cancer and is more common in African American women, suggesting potential for targeted therapy (Rodriguez et al., medRxiv, 2023) | BIRC2 is implicated in cervical cancer, related to BFB cycles resulting in the gene's amplification. The study from a preprint provides insight into a specific amplification event on chromosome 11, which includes the BIRC2 gene. | 4 |

| FANCA | Potentially implicated in general carcinogenesis | FANCA was identified as one of the genes with BaP-induced mutations predicted to impact protein function in post-stasis HMEC. The mutated FANCA gene is cited as a high-confidence cancer driver gene. This was observed in human mammary epithelial cells exposed to the carcinogen BaP, which is known to produce mutations typical of human lung cancers in smokers (Severson et al., Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen, 2014) | FANCA has evidence of a role as a cancer driver gene from a single study that analyzed molecular changes in human mammary epithelial cells after carcinogen exposure. This is an indirect functional association, not a direct clinical demonstration | 4 |

| MYB | Breast cancer | No evidence from the provided study links MYB as a cancer driver in breast cancer (Ping et al., Scientific Reports, 2016) | MYB was not identified as a cancer driver gene in the provided study. The study focused on breast cancer and MYB was not listed among the significantly associated genetic abnormalities | 1 |

Here are some other example use-cases for this script; in my experience, pretty common types of tasks in biotech:

- Analyze a set of genes and rank them by their importance in cancer metabolism, immune response, lupus, etc.

- Analyze a set of compounds and rank them by their toxicity, potency, etc.

- Analyze a set of bacterial strains and rank them by their presence in human microbiome, potential use as probiotics, etc.

With these kinds of queries, you'll likely get reasonable results, with the obvious candidates at the top (and perhaps a few surprises), comparable to what you might get from an inexperienced intern with unlimited time.

import json

import re

import requests

from pathlib import Path

from textwrap import dedent

from time import sleep

from urllib.parse import quote

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

# Requires OpenAI API Key: https://openai.com/blog/openai-api

# os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = "sk-xxx"

SEARCH_PUBMED_URL = "https://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/esearch.fcgi?db=pubmed&term={params}&retmax={max_abstracts}{api_key_param}"

GET_ABSTRACT_URL = "https://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/efetch.fcgi?db=pubmed&id={pmid}&retmode=text&rettype=abstract{api_key_param}"

# https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/bionlp/APIs/BioC-PubMed/

BIOC_PMCID_URL = "https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/bionlp/RESTful/pmcoa.cgi/BioC_json/{pmcid}/unicode"

DEFAULT_MAX_ABSTRACTS = 30

# NCBI recommends that users post no more than three URL requests per second and limit large jobs

# Failure to comply with this policy may result in an IP address being blocked from accessing NCBI.

# Add an API key if you want to download faster

NCBI_API_KEY = None

def remove_ref_blank_entries_and_offsets(obj):

"""

Recursively traverse through the JSON object (dict or list) and:

1. Remove any node if it or any of its nested structures contains a dict with 'section_type': 'REF'.

2. Remove any key-value pairs where the value is an empty list or empty dictionary.

3. Remove any key-value pairs where the key is 'offset'.

"""

if isinstance(obj, dict):

# Check if any value of this dict is a nested dict with 'section_type': 'REF'

if any(isinstance(v, dict) and v.get('section_type') == 'REF' for v in obj.values()):

return None

else:

# No nested dict with 'section_type': 'REF', recursively process each key-value pair

return {k: remove_ref_blank_entries_and_offsets(v) for k, v in obj.items() if k != 'offset' and

remove_ref_blank_entries_and_offsets(v) is not None and v != [] and v != {}}

elif isinstance(obj, list):

# Recursively process each item in the list

return [remove_ref_blank_entries_and_offsets(item) for item in obj

if remove_ref_blank_entries_and_offsets(item) is not None and item != [] and item != {}]

else:

# Return the item as is if it's not a dict or list

return obj

def main(genes, role, max_abstracts=DEFAULT_MAX_ABSTRACTS, ncbi_api_key=NCBI_API_KEY):

"""Download abstracts and fulltext from pubmed, generate a prompt, query OpenAI.

"""

Path("downloads").mkdir(exist_ok=True)

Path("gpt_output").mkdir(exist_ok=True)

api_key_param = "&api_key={ncbi_api_key}" if ncbi_api_key is not None else ""

for gene in genes:

abstracts = []

fulltexts = []

params = quote(f'({gene}) AND ("{role}")')

pmtxt = requests.get(SEARCH_PUBMED_URL.format(params=params, max_abstracts=max_abstracts, api_key_param=api_key_param)).text

pmids = re.findall("<Id>(\d+)</Id>", pmtxt)

sleep(0.3)

for pmid in pmids:

if Path(f"downloads/abstract.pmid_{pmid}.txt").exists():

abstracts.append(open(f"downloads/abstract.pmid_{pmid}.txt").read())

if Path(f"downloads/fulltext.pmid_{pmid}.json").exists():

fulltexts.append(json.load(open(f"downloads/fulltext.pmid_{pmid}.json")))

continue

abstract = requests.get(GET_ABSTRACT_URL.format(pmid=pmid, api_key_param=api_key_param)).text

open(f"downloads/abstract.pmid_{pmid}.txt", 'w').write(abstract)

abstracts.append(abstract)

sleep(0.3)

pmcid = re.findall("^PMCID:\s+(PMC\S+)$", abstract, re.MULTILINE)

assert len(pmcid) <= 1, "there should be max one PMCID per paper"

pmcid = pmcid[0] if len(pmcid) == 1 else None

if pmcid is not None:

fulltext_request = requests.get(BIOC_PMCID_URL.format(pmcid=pmcid))

if fulltext_request.status_code == 200:

fulltext_json = remove_ref_blank_entries_and_offsets(fulltext_request.json())

json.dump(fulltext_json, open(f"downloads/fulltext.pmid_{pmid}.json", 'w'), indent=2)

fulltexts.append(fulltext_json)

sleep(0.3)

# If there are only a couple of papers then we can include the fulltext

# 250k characters should be well below 100k tokens; 500k characters is too many

abstract_len = len("\n".join(abstracts))

fulltext_len = len("\n".join(json.dumps(j) for j in fulltexts))

if abstract_len + fulltext_len < 250_000:

abstracts_txt = "\n".join(abstracts) + "\n" + "\n".join(json.dumps(j) for j in fulltexts)

else:

abstracts_txt = "\n".join(abstracts)

gpt_out = f"gpt_output/{gene}_{role.replace(' ','_')}.txt"

if len(abstracts_txt) > 1_000 and not Path(gpt_out).exists():

completion = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4-1106-preview",

messages=[

{"role": "system",

"content": dedent("""

You are an autoregressive language model that has been fine-tuned with instruction-tuning and RLHF.

You carefully provide accurate, factual, thoughtful, nuanced answers, and are brilliant at reasoning.

If you think there might not be a correct answer, you say so.

Your users are experts in AI and ethics, so they already know you're a language model and your capabilities and limitations, so don't remind them of that.

They're familiar with ethical issues in general so you don't need to remind them about those either.

Don't be verbose in your answers, but do provide details and examples where it might help the explanation.

Your users are also experts in science, and especially biology, medicine, statistics.

Do NOT add any details about how science or research works, tell me to ask my doctor or consult with a health professional.

Do NOT add any details that such an expert would already know.

""")},

{"role": "user",

"content": dedent(f"""

Help me research whether this gene has the role of {role}: {gene}.

Here are the top abstracts from pubmed, and any full text that will fit in context:

{abstracts_txt}

Read and synthesize all the evidence from these papers.

Prefer evidence from good journals and highly cited papers, and papers that are recent.

If there is one standout result in a top journal like Nature, Science or Cell, focus on that.

There should usually be one primary result and most of the evidence should depend on that.

Include a score out of 10, where 1 would be a single paper with weak evidence,

5 would be a mid-tier journal with a single paper with believable evidence,

and 10 would be multiple Nature, Science or Cell papers with very strong evidence.

A score above 7 is exceptional, implying at least the result has been replicated and is trustworthy.

Make sure the results are valid json with fields exactly as in the examples below.

Do NOT change the fields, change the order, or add any other fields.

The "Gene" json entry MUST match the query gene. Here, {gene}.

Include AT LEAST ONE reference for each entry on evidence (unless there is no evidence), e.g., (Smith et al., Nature, 2021). ALWAYS include the journal name.

To help you think step-by-step about your response, use the FIRST "Summary" entry to summarize the question

and the relevant available evidence in your own words, in one hundred words or fewer.

Do NOT output markdown, just raw json. The first character should be {{ and the last character should be }}.

Here are some examples of json you might output:

{{

"Summary": "ABC1 has no evidence of {role}. The experiments are not convincing. There is some evidence for ABC2, which may indicate something."; // string

"Gene": "ABC1", // string

"Cancer type": "", // string

"Evidence": "No evidence as {role}", // string

"Score": 0 // integer from 0-10

}}

{{

"Summary": "There is some evidence for ABC2, which may indicate something. The evidence is medium, e.g. a paper in a mid-tier journal" // string

"Gene": "DEF2", // string

"Cancer type": "Bladder cancer", // string

"Evidence": "A CRISPR screen identified DEF2 as {role} in bladder cancer (Jones et al., Nature Cancer, 2001)", // string

"Score": 5 // integer from 0-10

}}

{{

"Summary": "GHI3 has been cited as {role} many times. The experiments are convincing. The evidence is strong: a recent Nature paper and a Science paper" // string

"Gene": "GHI3" // string

"Cancer type": "Colorectal cancer" // string

"Evidence": "A cell-based assay using a small molecule inhibitor identified GHI3 as {role} in colorectal cancer (Smith et al., Science, 2022, Thomson et al., Nature, 2019)", // string

"Score": 8 // integer from 0-10

}}

""")

}

]

)

open(gpt_out, 'w').write(completion.choices[0].message.content)

else:

# just log null results

open(gpt_out, 'w').write("")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main(genes = ["MAP2K1", "F5"], role = "cancer driver")