Molecular dynamics (MD) means simulating the forces acting on atoms. In drug discovery, MD usually means simulating protein–ligand interactions. This is clearly a crucial step in modern drug discovery, yet MD remains a pretty arcane corner of computational science.

This is a different problem to docking, where molecules are for the most part treated as rigid, and the problem is finding the right ligand orientation and the right pocket. Since in MD simulations the atoms can move, there are many more degrees of freedom, and so a lot more computation is required. For a great primer on this topic, see Molecular dynamics simulation for all (Hollingsworth, 2018).

What about deep learning?

Quantum chemical calculations, though accurate, are too computationally expensive to use for MD simulation. Instead, "force fields" are used, which enable computationally efficient calculation of the major forces. As universal function approximators, deep nets are potentially a good way to get closer to ground truth.

Analogously, fluid mechanics calculations are very computationally expensive, but deep nets appear to do a good job of approximating these expensive functions.

A deep net approximating Navier-Stokes

Recently, the SPICE dataset (Eastman, 2023) was published, which is a reference dataset that can be used to train deep nets for MD.

We describe the SPICE dataset, a new quantum chemistry dataset for training potentials relevant to simulating drug-like small molecules interacting with proteins. It contains over 1.1 million conformations for a diverse set of small molecules, dimers, dipeptides, and solvated amino acids.

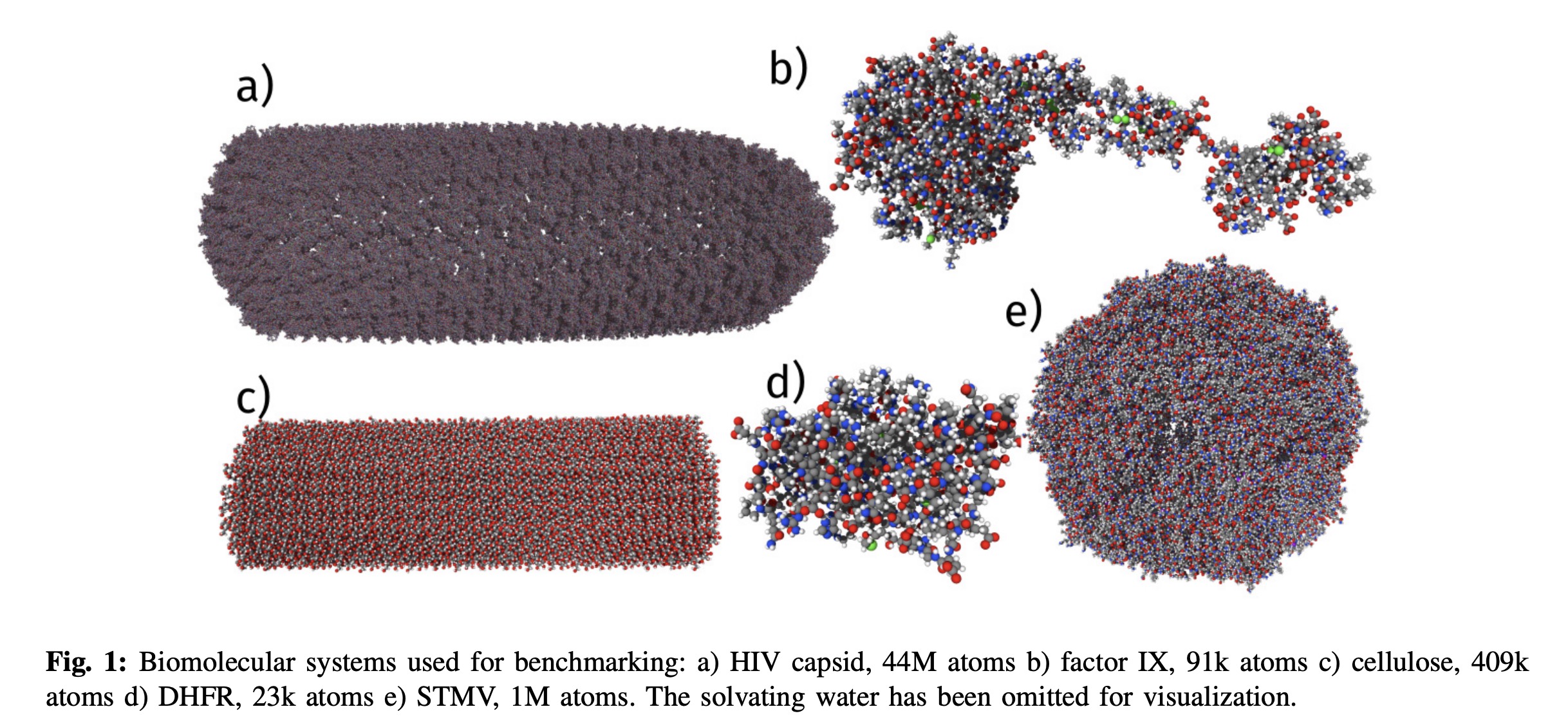

This dataset has enabled new ML force fields like Espaloma (Takaba, 2023) and the recent Allegro paper (Musaelian, 2023), where they simulated a 44 million atom system of a HIV capsid. Interestingly, they scaled their system as high as 5120 A100's (which would cost $10k an hour to run!)

There are also hybrid ML/MM approaches (Rufa, 2020) based on the ANI2x ML force field (Devereux, 2020).

All of this work is very recent, and as I understand it, runs too slowly to replace regular force fields any time soon. Despite MD being a key step in drug development, only a small number of labs (e.g., Chodera lab) appear to work on OpenMM, OpenFF, and the other core technologies here.

Doing an MD simulation

I have only a couple of use-cases in mind:

- does this ligand bind this protein in a human cell?

- does this mutation affect ligand binding in a human cell?

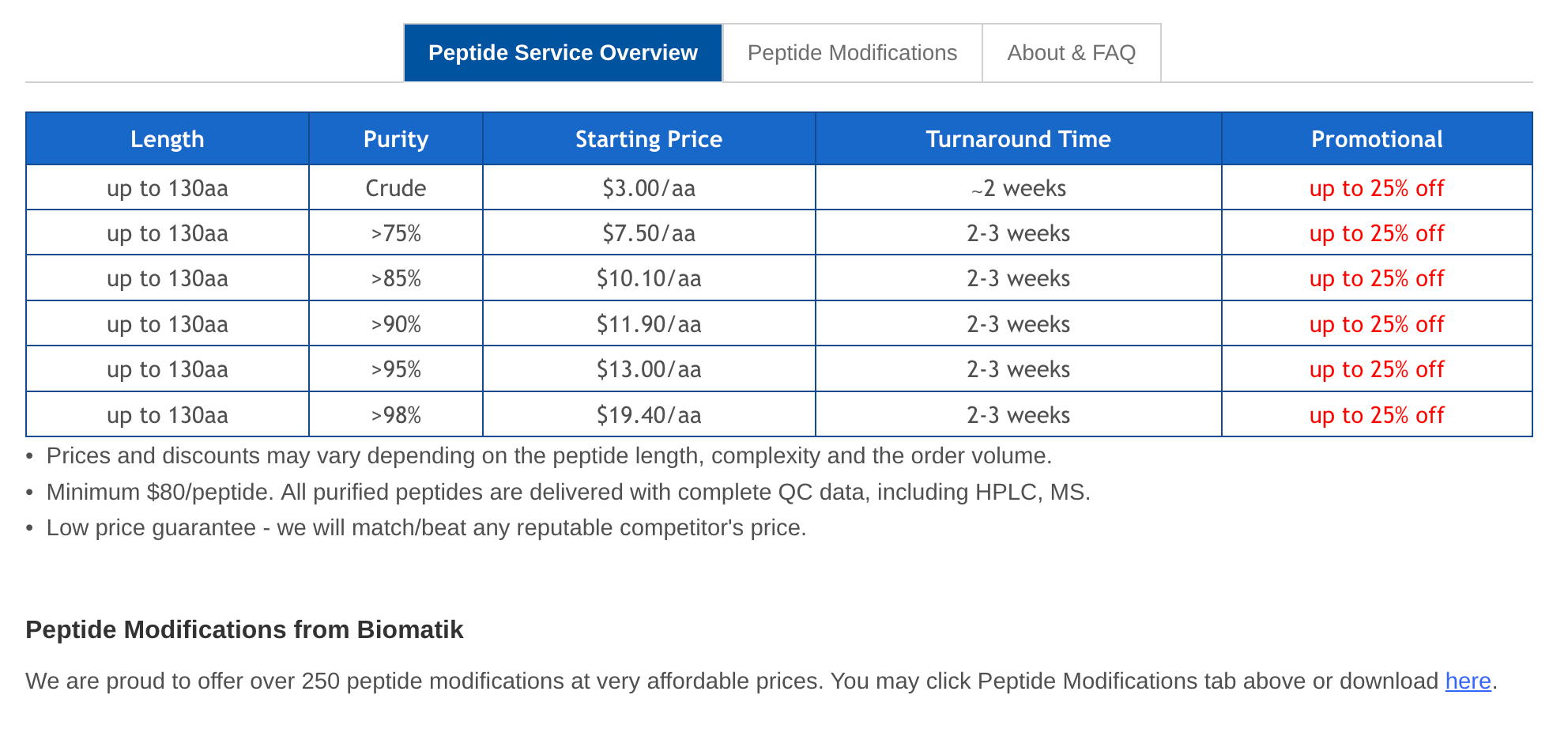

Doing these MD simulations is tricky since a lot of background is expected of the user. There are many parameter choices to be made, and sensible options are not obvious. For example, you may need to choose force fields, ion concentrations, temperature, timesteps, and more.

By comparison, with AlphaFold you don't need to know how many recycles to run, or specify how the relaxation step works. You can just paste in a sequence and get a structure. As far as I can tell, there is no equivalent "default" for MD simulations.

A lot of MD tutorials I have found are geared towards simulating the trajectory of a system for inspection. However, with no specific numerical output, I don't know what to do with these results.

Choosing an approach

There are several MD tools out there for doing protein–ligand simulations, and calculating binding affinities:

- Schrodinger is the main player in computational drug discovery, and a mature suite of tools. It's not really suitable for me, since it's expensive, geared toward chemists, designed for interactive use over scripting, and not even necessarily cutting-edge.

- OpenEye also appears to be used a lot, and has close ties to open-source. Like Schrodinger, the tools are high quality, mostly interactive and designed for chemists.

- HTMD from Acellera is not open-source, but it has a nice quickstart and tutorials.

- GROMACS is open-source, actively maintained, and has tutorials, but is still a bit overwhelming with a lot of boilerplate.

- Amber, like GROMACS, has been around for decades. It gets plenty of use (e.g., AlphaFold uses it as a final "relaxation" step), but is not especially user-friendly.

- OpenMM seems to be where most of the open-source effort has been over the past

five years or so, and is the de facto interface for a lot of the recent ML work in MD

(e.g., Espaloma). A lot of tools are built on top or OpenMM:

- yank is a tool for free energy binding calculations. Simulations are parameterized by a yaml file.

- perses is also used for free energy calculation. It is pre-alpha software but under active development — e.g., this recent paper on protein–protein interaction. (Note, I will not claim to understand the differences between yank and perses!)

- SEEKR2 is a tool that enables free energy calculation, among other things.

- Making it rain is a suite of tools and colabs. It is a very well organized repo that guides you through running simulations on the cloud. For example, they include a friendly colab to run protein–ligand simulations. The authors did a great job and I'd recommend this repo broadly.

- BAT, the Binding Affinity Tool, calculates binding affinity using MD (also see the related GHOAT).

OpenMM quickstart for protein simulation

Since I am not a chemist, I am really looking for a system with reasonable defaults for typical drug development scenarios. I found a nice repo by tdudgeon that appears to have the same goal. It uses OpenMM, and importantly has input from experts on parameters and settings. For example, I'm not sure I would have guessed you can multiply the mass of Hydrogen by 4.

This keeps their total mass constant while slowing down the fast motions of hydrogens. When combined with constraints (typically constraints=AllBonds), this often allows a further increase in integration step size.

I forked the repo, with the idea that I could keep the simulation parameters intact but change the interface a bit to make it focused on the problems I am interested in.

Calculating affinity

I am interested in calculating ligand–protein affinity (or binding free energy) — in other words, how well does the ligand bind the protein. There's a lot here I do not understand, but here is my basic understanding of how to calculate affinity:

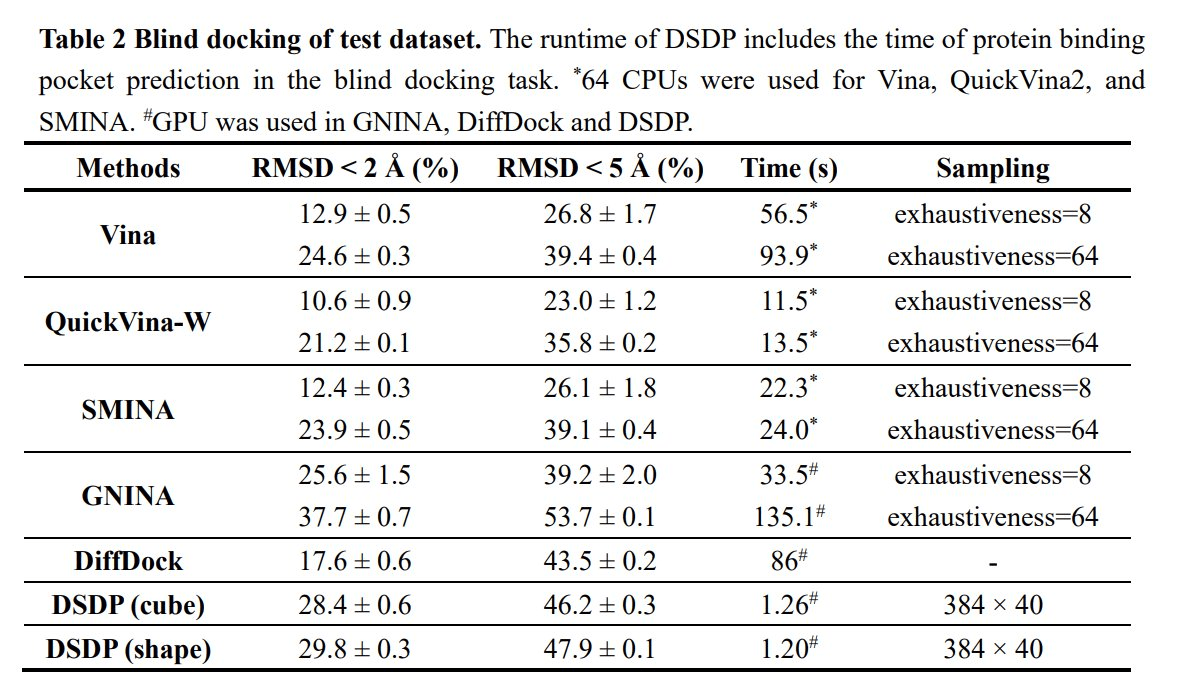

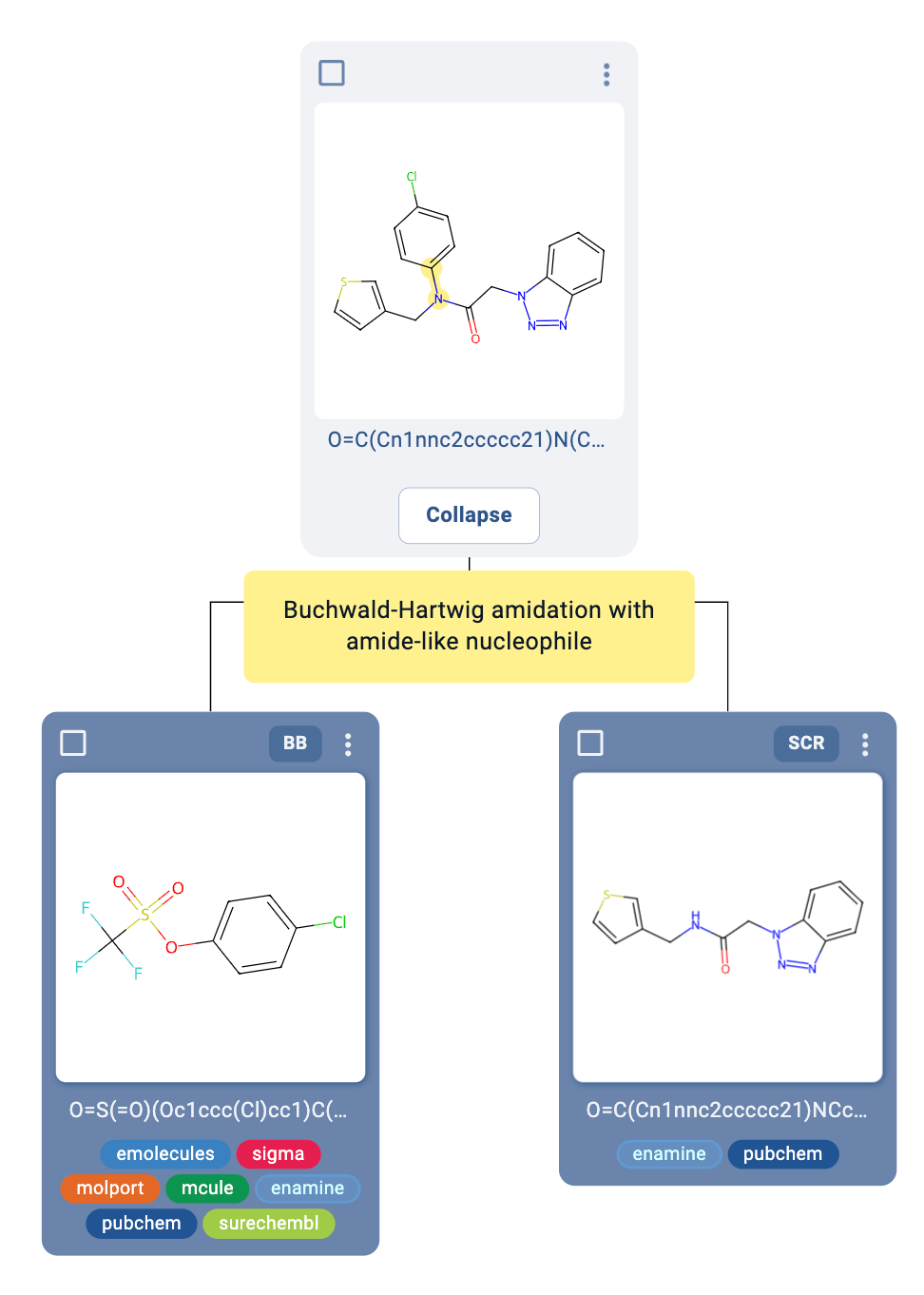

- Using MD: This is the most accurate way to measure affinity, but the techniques are challenging. There are "end-point" approaches (e.g., MM/PBSA) and Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) / alchemical approaches. Alchemical free energy approaches are more accurate, and have been widely used for years. (I believe Schrodinger were the first to show accurate results (Wang, 2015).) Still, I found it difficult to figure out a straightforward way to do these calculations.

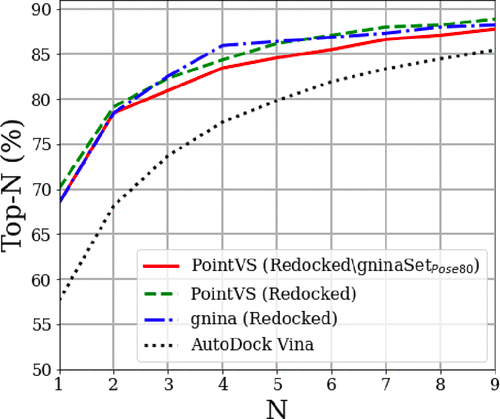

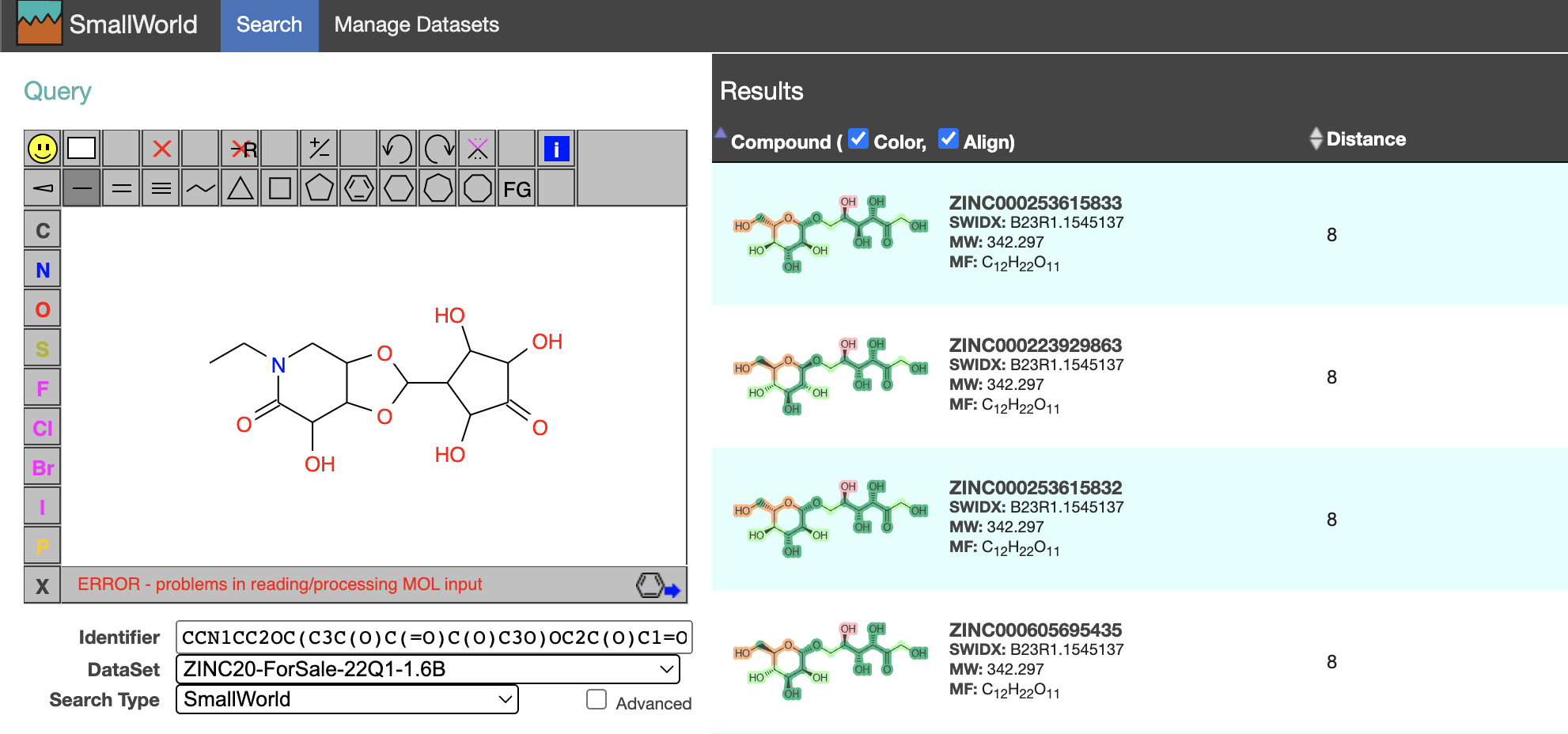

- Using a scoring function: This is how most docking programs like vina or gnina work. Docking requires a very fast, but precise, score to optimize.

- Using a deep net: Recently, several deep nets trained to predict affinity have been published.

For example, HAC-Net

is a CNN trained on PDBbind.

This is a very direct way to estimate binding affinity,

and should be accurate if there is enough training data.

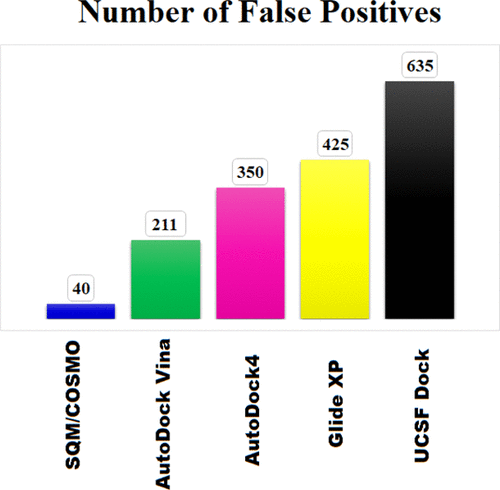

The SQM/COSMO docking scoring function (Ajani, 2017)

Unfortunately, I do know know of a benchmark comparing all the above approaches,

so I just tried out a few things.

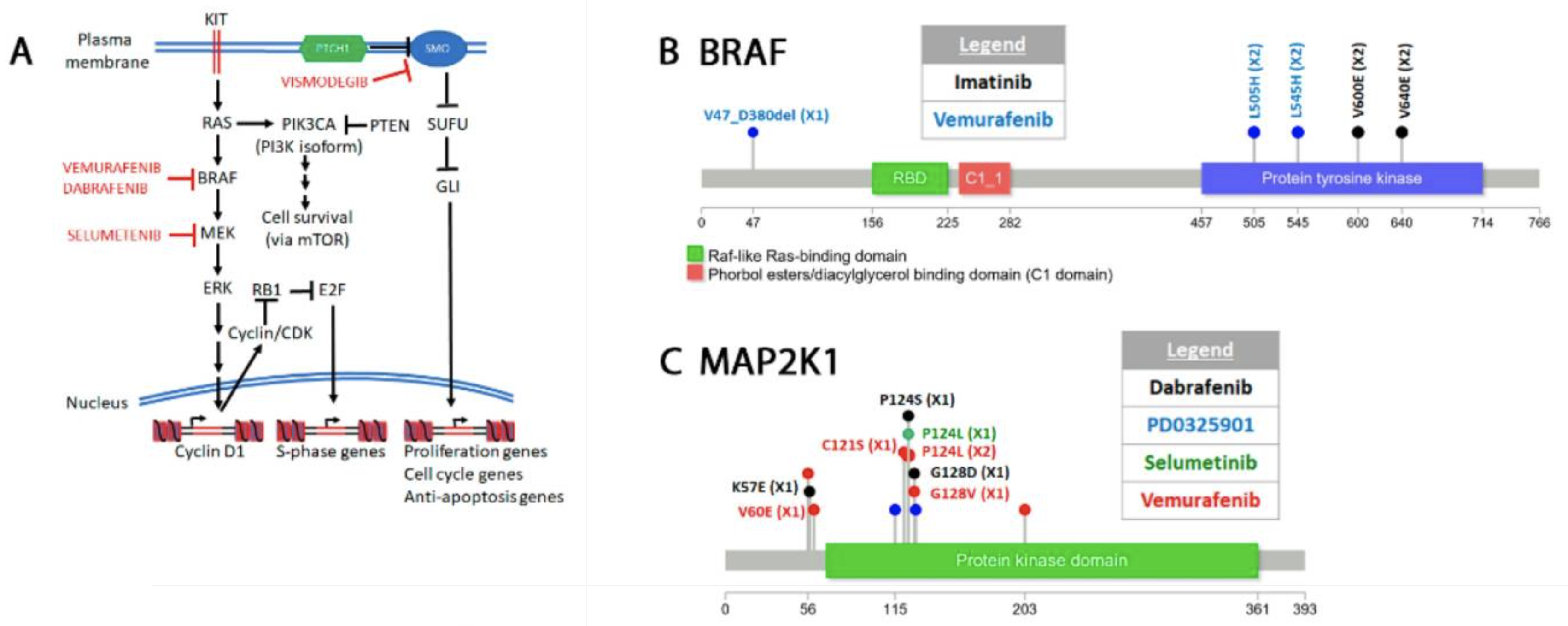

Predicting cancer drug resistance

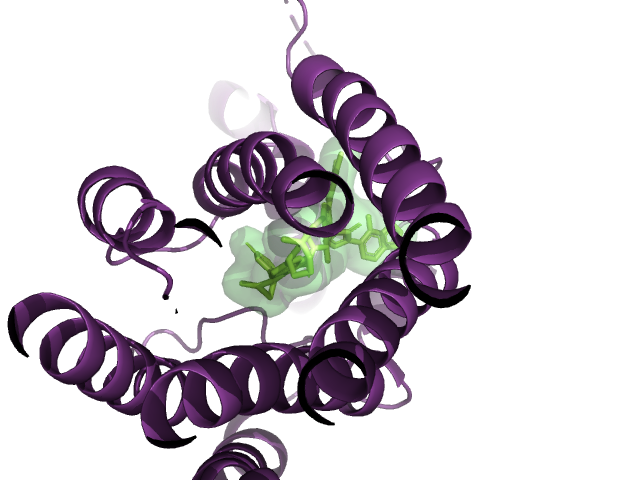

One interesting but tractable problem is figuring out if a mutation in a protein will affect ligand binding. For example, let's say we sequence a cancer genome, and see a mutation in a drug target, do we expect that drug will still bind?

There are many examples of resistance mutations evolving in cancer.

Common cancer resistance mutations (Hamid, 2020)

Experiments

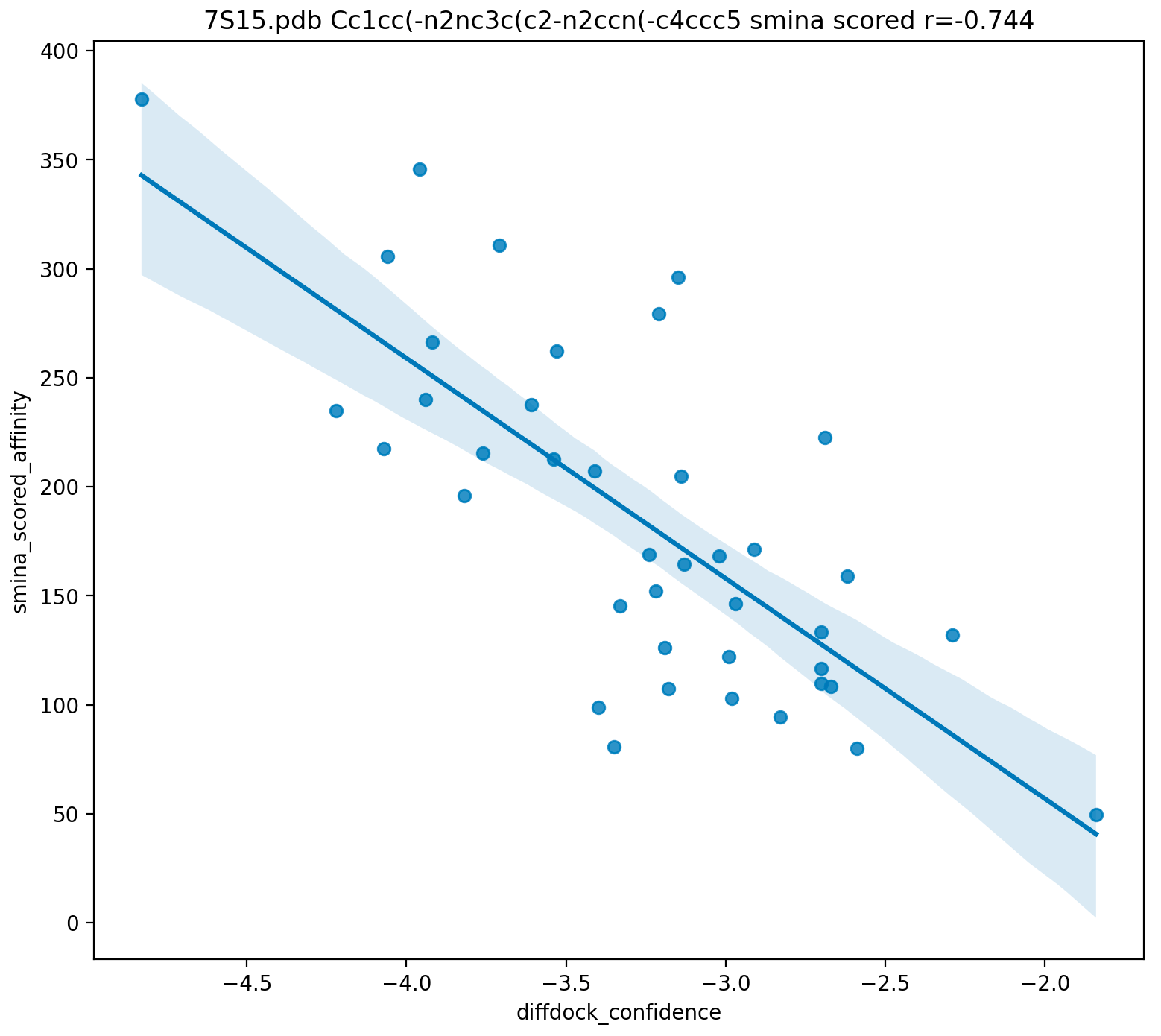

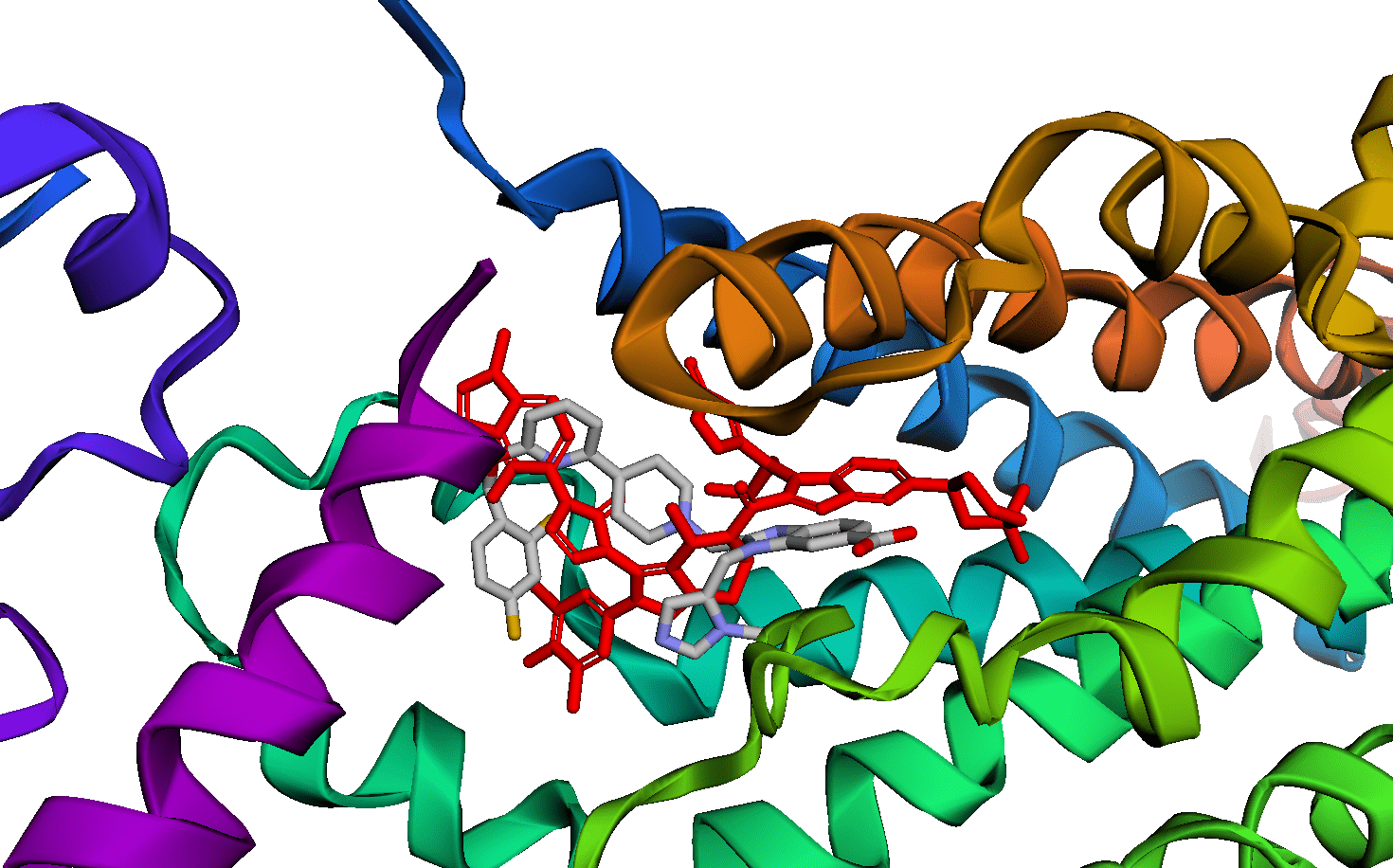

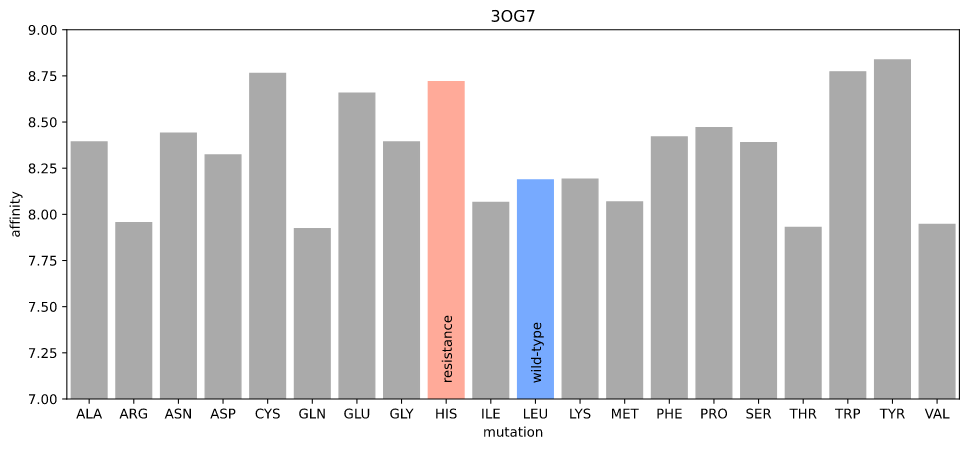

BRAF V600E is a famous cancer target. Vemurafenib is a drug that targets V600E, and L505H is known to be a resistance mutation. There is a crystal structure of BRAF V600E bound to Vemurafenib (PDB:3OG7). Can I see any evidence of reduced binding of Vemurafenib if I introduce an L505H mutation?

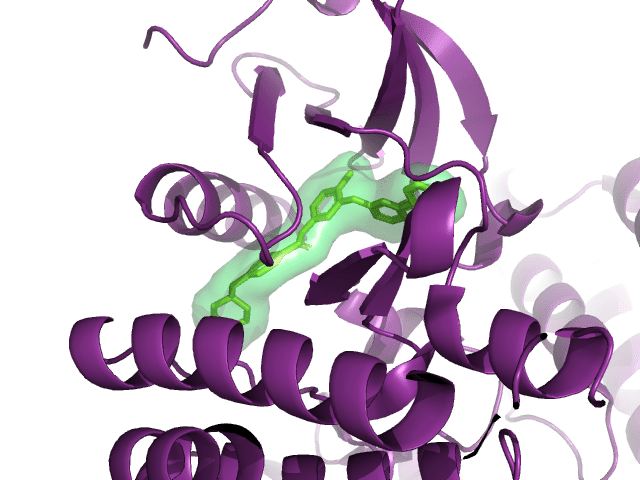

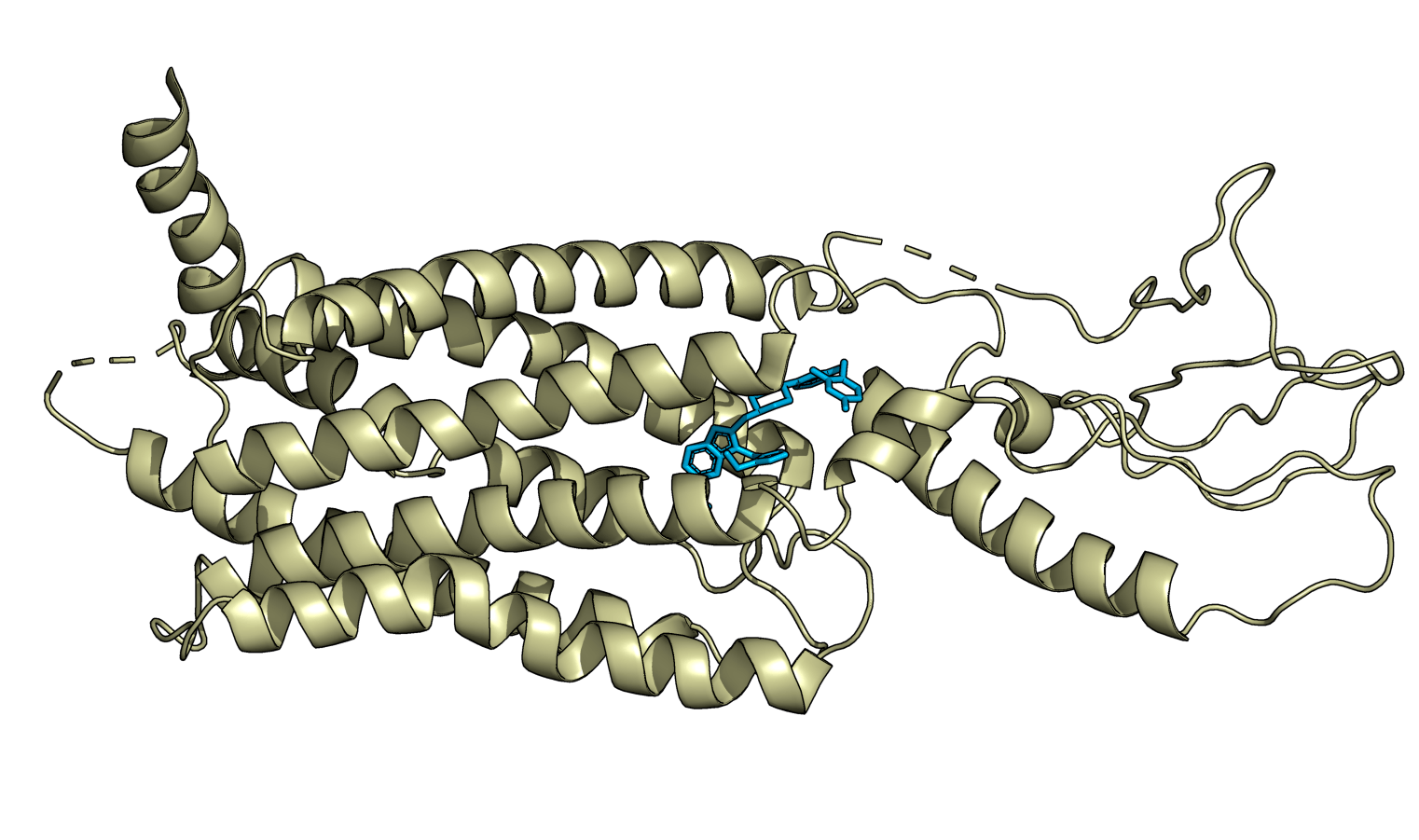

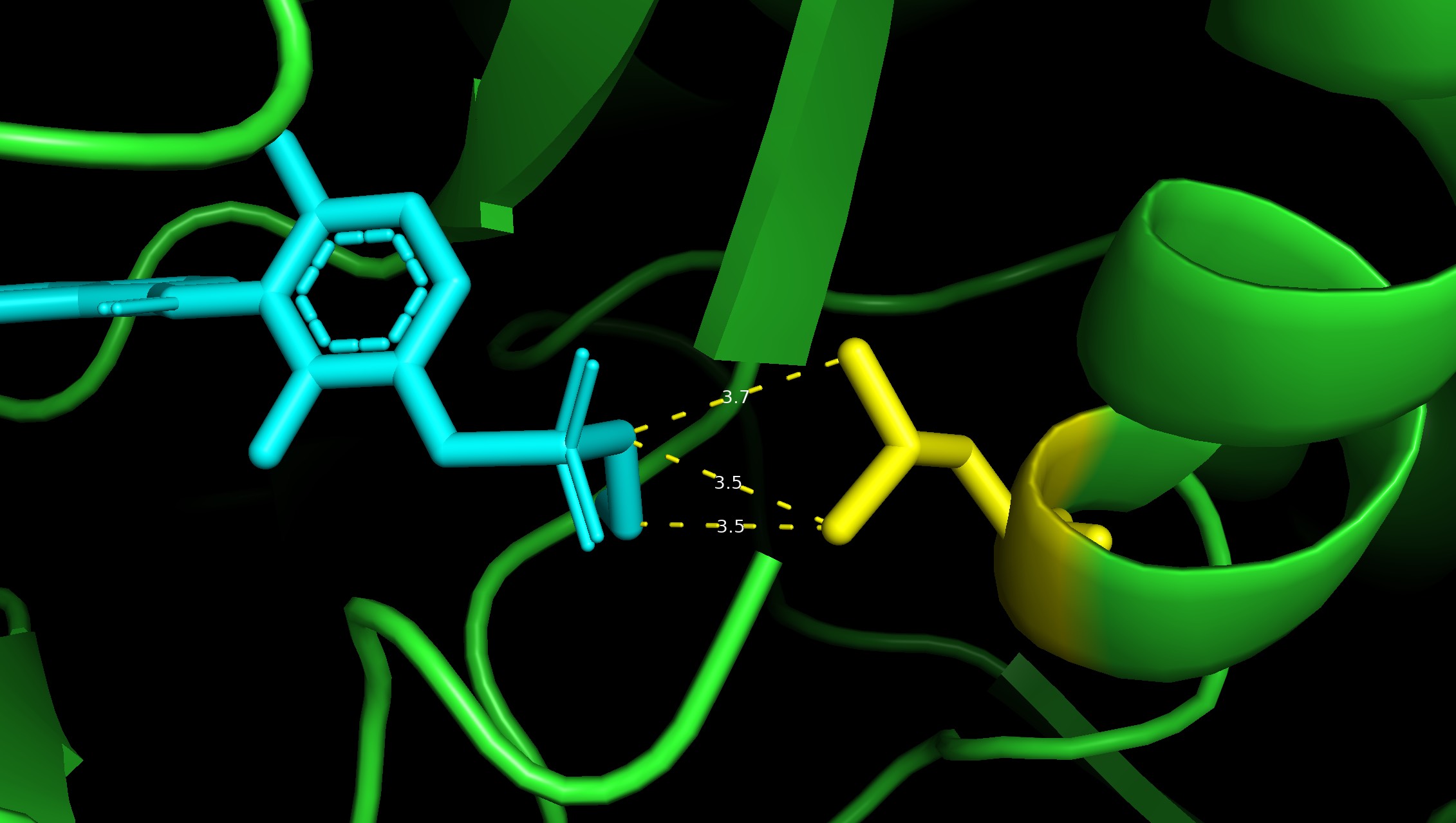

PDB:3OG7, showing the distance between vemurafenib (cyan) and L505 (yellow)

I ran a simple simulation: starting with the crystal structure, introduce each possible mutation at position 505, allow the protein–ligand system to relax, and check to see if the new protein–ligand interactions are less favorable according to some measure of affinity.

I first used gnina's scoring function, which is fast and should be relatively precise (in order for gnina to work!) The rationale here was that the "obstruction" due to the resistance mutation would be detectable as the new atom positions of the amino acid and ligand would lead to a lower affinity.

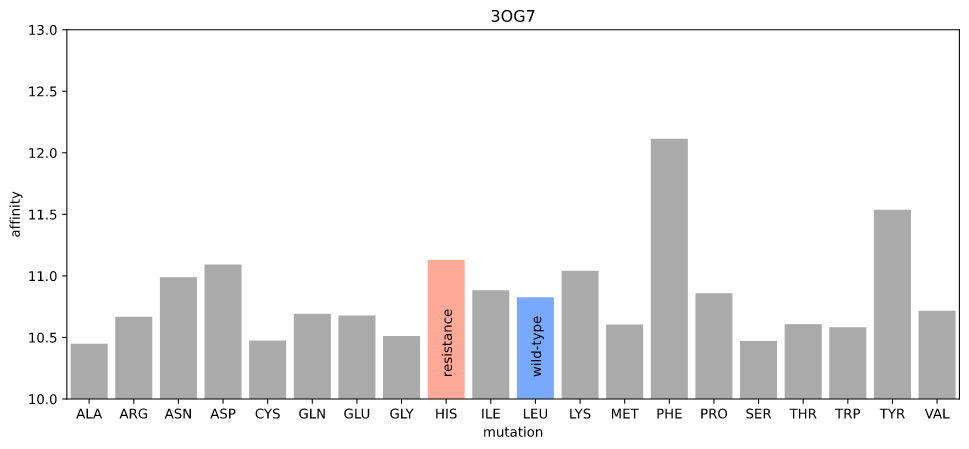

Estimated affinity given mutations at position 505 in 3OG7

Nope. The resistance mutation has higher affinity (realistically, there are no distinguishable differences for any mutation).

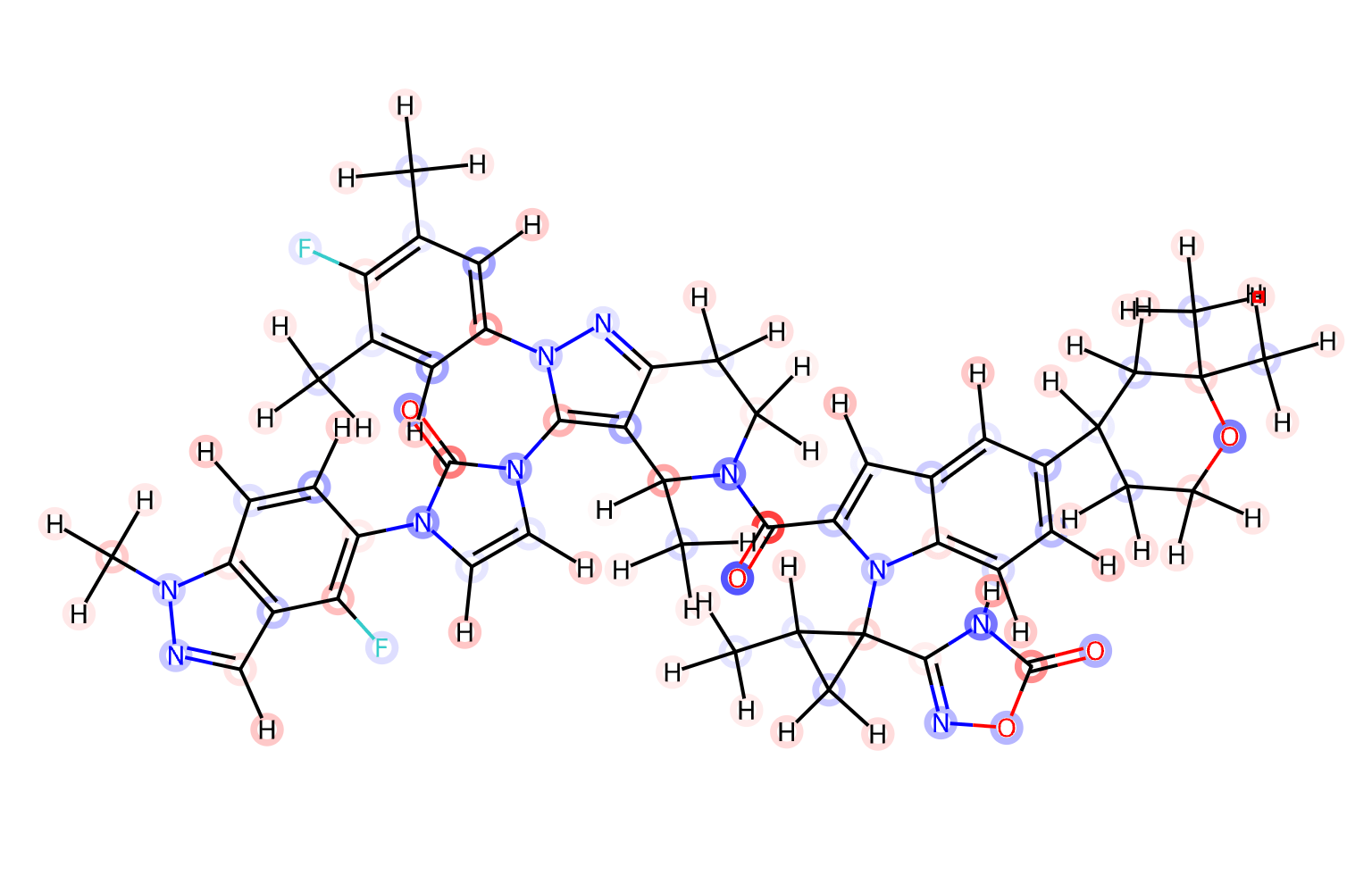

We also know that MEK1 V215E acts as a resistance mutation to PD0325901, and the PDB has a crystal structure of MEK1 bound to PD0325901 (PDB:70MX).

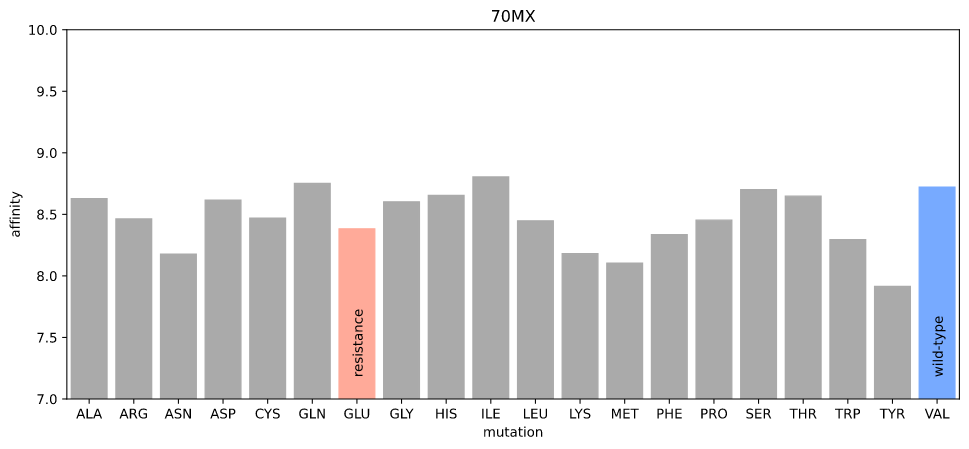

Estimated affinity given mutations at position 215 in 70MX

Again, I can't detect any difference in affinity due to the resistance mutation.

HAC-Net

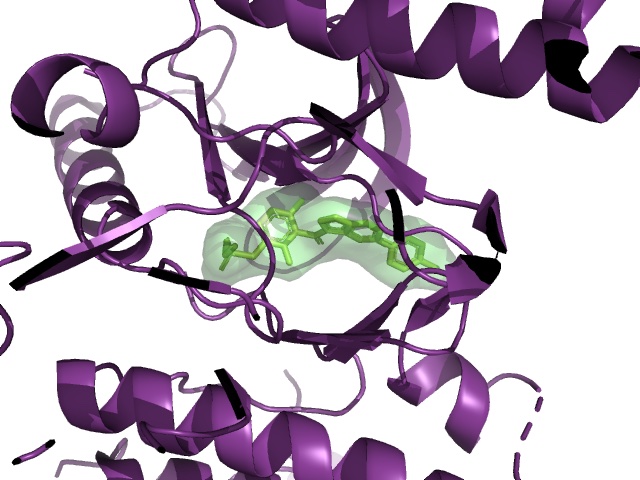

I also tried a deep-learning based affinity calculator, HAC-Net. HAC-Net has a nice colab and is relatively easy to run Dockerized.

The HAC-Net colab gives me a pKd of 8.873 for 3OG7 (wild-type)

Estimated pKd given mutations at position 505 in 3OG7 using HAC-Net

I still see no difference in affinity with HAC-Net.

Each of these simulations (relaxing a protein–ligand system with solvent present) took a few minutes on a single CPU. If I wanted to simulate a full trajectory, which could be 50 nanoseconds or longer, it would take hundreds or thousands of times as long.

Conclusions

On the one hand, I can run state-of-the-art MD simulations pretty easily with this system. On the other hand, I could not discriminate cancer resistance mutations from neutral mutations.

There are several possible reasons. Most likely, the short relaxation I am doing is insufficient and I need longer simulations. The simulations may also be insufficiently accurate, either intrinsically or due to poor parameterization. It's difficult to feel confident in these kinds of simulations, since there's no simple way to verify anything.

If anyone knows of any obvious fix for the approach here, let me know! Probably the next thing I would try would be adapting the Making It Rain tools, which include (non-alchemical) free energy calculation. For some reason the Making It Rain colab specifies "This notebook is NOT a standard protocol for MD simulations! It is just simple MD pipeline illustrating each step of a simulation protocol." which begs the questions, why not and where is such a notebook?

I do think that enabling anyone to run such simulations — specifically, with default parameters blessed by experts for common use-cases — would be a very good thing.

There are already several cancer drug selection companies like Oncobox, so maybe there should be a company doing this kind of MD for predicting cancer resistance. Maybe there is and I just have not heard of it?

Addendum: modal labs

I have been experimenting with modal labs for running code like this, where there are very specific environment requirements (i.e., painful to install libraries) and heavy CPU/GPU load. Previously, I would have used Docker, which is fundamentally awkward, and still requires manually provisioning compute. Modal can be a joy to use and I'll probably write up a separate blogpost on it.

To do your own simulation (bearing in mind all the failed experiments above!), you can either use my MD_protein_ligand colab or if you have a modal account, clone the MD_protein_ligand repo and run

mkdir -p input && modal run run_simulation_modal.py --pdb-id 3OG7 --ligand-id 032 --ligand-chain A

This basic simulation (including solvent) should cost around 10c on modal. That means we could relax all 5000 protein–ligand complexes in the PDB for around $500, perhaps in just a day or two (depending on how many machines modal allows in parallel). I'm not sure if there's any point to that, but pretty cool that things can scale up so easily these days!

Comment